This page contains the entire Communicate Your Advance Directives for Health Care lesson to enable you to print a section or the whole lesson.

Return to the Communicate Your Advance Directives for Health Care lesson.

If you had a serious accident or illness that caused permanent loss of mental capacity, leaving you unable to tell your doctor which medical treatments you did or did not want, would your loved ones know what to do? Who would make these decisions for you? If you couldn’t make your wishes known, how could you make sure they were respected?

If you’re like most people, you probably haven’t taken time to complete or discuss documents known as advance directives for health care. Advance directives include a living will and durable power of attorney for health care. They allow you to give instructions on these topics to your health-care providers and loved ones, relieving them of the burden of guessing what you want.

The choices you make as you prepare these documents should be based on your personal values, beliefs, preferences, and discussions with loved ones. Since it’s impossible to foresee future circumstances or illness, think in general terms about what’s important to you.

In this learning lesson you will:

- Learn about advance directives for health care, including living wills and durable powers of attorney for health care

- Explore ways to communicate your health-care wishes

- Increase your knowledge by taking a quiz on advance directives for health care and reviewing several case studies

- Become aware of ways to hold a family meeting to discuss end-of-life issues

- Gain insights from others through streaming videos of individuals and families who prepared advance directives for health care and communicated their choices

Advance directives for health care are legal documents that enable you to plan for and communicate your end-of-life decisions. Should you become unconscious or too ill to write or speak, they give you a voice in your medical treatment. Without advance directives, these critical decisions could be made by people—including doctors, judges, and family members—with whom you’ve never shared your wishes.

There are two basic documents that allow you to write out your wishes for medical care, both grouped under the broad heading of health-care directives. It’s wise to prepare both.

- A living will allows you to document your wishes concerning medical treatments at the end of life.

- A durable power of attorney for health care (or health-care proxy) allows you to appoint a person you trust as your health-care agent (or surrogate decision-maker). This person is authorized to make medical decisions on your behalf if accident or illness prevents you from communicating.

Advance directives for health care, which can be called by several names in different states, are legally valid throughout the United States. In some states, the living will and durable power of attorney for health care are combined into one document. Because laws governing advance directives vary from state to state, it’s important to complete and sign advance directives that comply with your state’s laws.

A living will documents your instructions regarding how you wish to be cared for once you are unable to make your own medical decisions. It includes your wishes about life-sustaining medical treatments and describes to others—including your doctors, family, and court personnel—the extent and intensity of end-of-life medical care that you desire.

Preparing a living will takes a little time and more than a little thought. Rather than simply check-marking boxes on a form, allow time to discuss your wishes with your family physician and loved ones.

A durable power of attorney for health care allows you to choose someone (generally referred to as a health-care or medical “agent,” “representative,” or “proxy”) who will make health-care decisions for you when you can no longer communicate. You may designate your spouse, another family member, a close personal friend, or other trusted person of legal age—preferably, someone who lives near you. Talk to the person you choose to be sure he or she is capable of carrying out your health-care wishes and is willing to do so. Provide him or her with a copy of your living will. It’s wise to select at least one other person as an alternate in case your primary health-care agent is unable to function when needed. In some states, your durable power of attorney for health care must be witnessed and notarized in order to be legally binding. If your state does not have an approved format to follow, you’ll want to work with an attorney as you prepare this document.

Designated health-care agents have no power to act on your behalf while you can still communicate your own wishes, and their power ends at your death. Durable power of attorney for health care is used only for medical—not financial—decisions.

Each state has its own laws regarding advance directives, and many states have their own forms. Federal law requires hospitals to provide information about advance directives to people in their communities; contact the patient representative or social services department at a hospital near you and request copies. You may also be able to pick up advance-directive forms from your local Office on Aging, state Attorney General’s office, or nearby AARP chapters, senior centers, and assisted living or nursing facilities.

In most—but not all—states, you won’t need to hire an attorney to prepare these documents. Information regarding your particular state’s laws can often be found on web sites for your state’s Attorney General, Statutes, Department of Health, Department of Social Services, Department of Motor Vehicles (driver’s license division), bar association, or medical library. When using the Internet, make sure you are accessing the latest and most accurate information about your state’s health-care advance directives.

Your living will and durable power of attorney for health care are important legal documents. Keep your signed original documents in a secure, but accessible, place. Do not put the originals in your safe-deposit box or in another location from which it would be difficult for you or your health-care agent to retrieve them at whatever time they might be needed.

Give photocopies of the signed, dated originals to whomever you have designated to carry out your wishes. In addition to your health-care agent and alternate agent(s), the recipients of these copies should include your doctor(s), key family members, clergy, and even close friends who might become involved in your health care and medical treatment. It’s wise to keep a copy in your vehicles or to carry a wallet card that refers to the documents’ existence and location and names your health-care agent(s). If you enter a hospital, nursing home, or hospice, ask that photocopies be filed with your medical records.

In case you decide to make changes in your advance directives, keep a list of who has current copies so that you can provide them with updated versions.

In some states, you can post your living will on a computer registry that your doctors and loved ones can easily access by password. Check with a local hospital to see if this service is available in your state.

You may change or cancel your advance directives at any time, as long as you are considered of sound mind to do so. Being of sound mind means that you are still able to think rationally and communicate your wishes in a clear manner. Your changes must be made on the advance-directive forms that comply with your state’s laws. Discard the original and copies of advance directives that no longer reflect your wishes. Make sure that your doctor and any family members who knew about your directives are aware that you have changed them, and give copies of your new documents to your doctor, health-care agent, clergy, family members, or trusted friends.

You should update your advance directives if your wishes change, if you move to a different state, and if the person you named as your health-care agent becomes unable to supervise your wishes or you no longer want that individual to serve in this capacity. You should also consider preparing new documents if you made and finalized documents many years ago.

Are you a person who:

- is reluctant to talk about death?

- is experiencing declining health and doesn’t want to discuss loss of decision-making control?

- has a hard time making decisions, so nothing gets done?

- feels medical choices should be kept private?

- never thinks much about end-of-life health-care issues?

- thinks about getting professional help for legal affairs, but never gets around to it?

Communication strategies that work for many include:

- Plan Ahead

- Hold a Family Meeting

- Talk Among Family Members

Many families do not discuss health-care plans until a crisis occurs. Then it may be too late. Once a person suffers mental incapacity, options are reduced and procedures become more complicated and costly. Others who may be unaware of a person’s wishes—such as social workers, physicians, lawyers, judges, court-appointed guardians, and conservators—may become involved in the decisions.

Planning ahead can:

- protect your family from being forced to make decisions in crisis

- ease decision-making during inevitably difficult times

- decrease the likelihood of family dissention and possible court actions

- reduce disagreements between brothers and sisters about “what Mom or Dad wants”

- reduce stress—emotional and financial—later on

- assure that an individual’s life-style, personal philosophies, and choices are known and protected

- increase the options open to older people and their families

There are many appropriate times to have discussions about the future. One time many people consider completing advanced directives is when they are making arrangements for a long vacation. Other times are when a friend, neighbor, or other family member has recently died.

Planning ahead does not prevent all problems, but it does allow individuals to consider options before they’re needed, and it enables family and friends to make more effective decisions when end-of-life approaches.

To become more familiar with the issues before discussing them with others, take the Quiz for Health Care Advance Directives. The responses provided are accurate for residents of Idaho, Iowa, Kentucky, North Dakota, and South Dakota. Although laws regarding advance directives for health care may be different in your state, this quiz will give you important topics to consider.

The best situation to foster communication among family members may be a formalized meeting to address concerns. The initiator might contact each person by phone, letter, or e-mail to suggest holding a meeting at a convenient time. Conducting end-of-life discussions during emotionally demanding events, such as holidays and family celebrations, may not be the best time for some families. A time when all are fresh may be better. However, holidays and family celebrations may be the only occasion when you can gather together—and a discussion like this could make it a particularly meaningful event.

Involve appropriate family members. Be sensitive to a parent’s desire for privacy and balance it with the desire to have all members of the immediate family present. Who constitutes the “immediate family”? Should daughters-in-law and sons-in-law be included? How about adopted children—or children by another marriage? How old should participants be? Could the combined input of in-laws, nieces, and nephews overwhelm the rightful input of a single adult child?

If family relations are tense, some members may not consent to be present. If this is the case, try suggesting that the meeting be facilitated by an “outside person,” such as a family lawyer, adviser, social worker, family counselor, or therapist. Often the mere presence of an “outsider” will keep the mood calm and businesslike and the conversation on course. However, an outsider’s presence may also inhibit openness among family members. Decide what’s best for your situation.

It may not be important or best for all family members to know everything about their parents’ lives or financial affairs. What IS important is that parents have:

- gathered together their important papers

- made known, to at least one family member, the location of important papers

- prepared for the possibility of incapacity and communicated their wishes

- considered how to pay for long-term care should the need arise

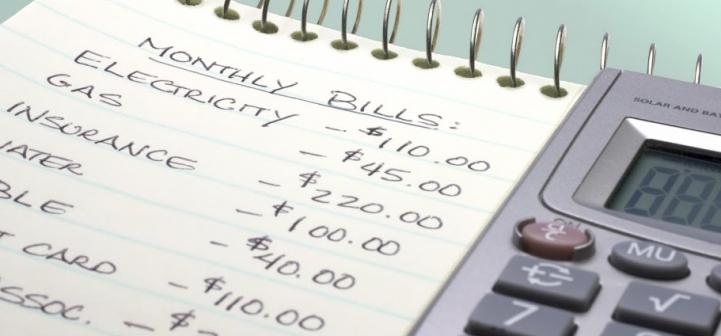

Before the meeting, make a list of other concerns to be discussed and questions to be answered. Also, decide who will take notes. At least one person should record any tasks that require follow-up, such as taking action to legalize the selection of an individual and alternates for the durable power of attorney for health care and checking into costs of long-term care and long-term care insurance.

To familiarize yourself with the important papers that all adults should keep and where they should be stored, review the “Legally Secure Your Important Papers: Organize Your Important Household Papers” learning lesson. Use the Organize Your Important Papers and Record of Important Papers online resources.

For more information on paying for long-term care, see http://www.financinglongtermcare.umn.edu

At your family meeting, you might want to include a discussion of a couple of case studies that illustrate situations your family might face some day.

- Advance Directives Case Study 1. When is it too soon to honor a living will? When does your health-care agent have the authority to make your medical decisions?

- Advance Directives Case Study 2. How do you handle after-death choices (organ/tissue donations, autopsy, burial, cremation)?

With each case study, we provide state-specific answers for Idaho, Iowa, Kentucky, North Dakota, and South Dakota. Responses for your state may vary. An elder law or estate-planning attorney licensed in your state can assist you with these types of situations.

Talking with our families about end-of-life issues, such as living wills and health-care agents, isn’t easy. To learn about discussion strategies that work, click on the video buttons that follow. You’ll view streaming videos and read about people who have discussed end-of-life issues with their own families. Most, but not all, have already completed their advance directives for health care.

“It’s kind of like, hey, I’m bullet-proof, nothing is going to happen to me. But it’s something to really think about.” – Jerry

Few of us find it easy to talk to family members about end-of-life issues. We may have ideas about what kinds of medical treatment we would or would not want and who we would trust to make the best possible decisions for us when we are no longer able to make them for ourselves. Sharing these thoughts with our families can seem awkward, and approaching other family members about what they would want seems even more difficult. It’s not surprising, then, that we have many reasons for delaying preparation of our “advance directives”—our living wills and our appointments of health-care agents to speak on our behalf when death is imminent.

Read on for discussion strategies.

You’ll be living forever, right?

Lydia, grandmother

Transcript: “You just don’t want to face it that one day you’re going to die. You don’t want to think about that. You just want to think that you’re going to be living forever and that’s not the case.”

No talking about sex, politics, or advance directives

Tom, manager of chaplaincy services

Transcript: “People kiddingly will say, you know, we can talk about anything but sex and politics and I think you can probably add dying and advanced directives safely to that list. I think we’re uncomfortable talking about this. I think that some people have a sort of thought that, if we talk about it, it may happen.”

What’s a living will, anyway?

Louard, job trainer

Transcript: “Many people are really unaware of just what the living will is for. You hear ‘will’ all the time, but ‘living will’, what does that mean to the average person? ‘Will’ for death, ‘living will’ for health care—and in fact I don’t think the average person on the street really has that in his mind. You’re hearing ‘will’ and you don’t hear the ‘living will’ part; you just hear the ‘will’ part and you’re thinking, oh, boy, I’m going to die, what’s going to happen to all of my money, where’s my house going, the kids are going to be fighting over everything. But you’re not thinking about, well now, what happens if I go into a coma, what’s going to happen to me, what’s going to take place, who’s going to take care of me, things like that.”

“As difficult and challenging as this conversation is—and it clearly is—it pales in comparison with the pain and the suffering that not having it puts people through.” – Tom, manager of chaplaincy services

When end-of-life decisions are made and communicated long before there’s a need to put them into effect, family members can be confident that they know each other’s wishes. They can have time to grow comfortable with decisions that may have been difficult at first to understand and accept. As the end nears, they can spare themselves the unnecessary grief that not knowing what to do inevitably brings. And their loved one’s passing can be a time of tenderness and clarity, rather than confusion or strife.

Read on, or click on the video buttons below for discussion strategies.

Without advance directives, contention and debates are likely

Mamie, college social work professor

Transcript: “So often people are not thinking it’s important, and then if people do not do it then when they reach a point where they can’t do it then you see a lot of contention going on and debates going on among family members and other people that really don’t agree or sometimes do agree, and it becomes more difficult to accomplish what needs to be done for the person who can’t do it for themselves.”

I wish I knew what my husband wants

Mari, community development specialist

Transcript: “I worry about him that he doesn’t have anything. I don’t know what I would do if I were put into a situation because I really don’t know what it is that he wants. You think you know somebody but he may have a completely different idea of what he wants done in that situation, and so he hasn’t shared that with me.”

It should be my decision, not someone else’s

Tom, manager of chaplaincy services

Transcript: “I feel strongly, sort of passionately, about this. I think that when we’re talking about end-of-life decisions, which would give us decisions or directives in advance, the most important event in our life– I don’t want to turn over the decision to buy a car or buy a house to someone else, and those are minor decisions in comparison to this. I think it’s essential. And because it’s unavoidable, because death is unavoidable, the only option that we have in not making the decision is having somebody else make it for us.”

“You never know what’s going to happen. You don’t have to be old to die.” – Lydia

Any time after you’ve turned 18 is a good time to write your living will and to choose a health-care agent that you trust. Some families start talking with one another about these issues and documents when they’re planning a long trip overseas or have just survived a close call with a family member’s health. Others begin when their children are born or reach maturity or when a spouse or parent dies. Many people are prompted by news stories—disturbing real-life cases like those of Terri Schiavo or Karen Quinlan. It’s neither necessary, nor preferable, for us to wait until we are elderly or infirm.

Read on, or click on the video buttons below for discussion strategies.

Everybody should do it, old or young

Mari, community development specialist

Transcript: “I discussed it with my friends, just because I felt that, you know, I went through the process and it was pretty easy, self-explanatory, and I think that everybody should do it, no matter how old or young you are. Once you’re legal age and have some life experience and know what it is that you want to happen in that situation, you should do it.”

Our children may die before we do

Vernell, teacher

Transcript: “With the way things are going nowadays, I mean, who’s to say, you know. It’s so possible that our children may precede us, and I want to know what their wishes are and I would like their wishes to be carried out, too, because it’s allowed for them just as it is for us. Just because they’re younger doesn’t mean they don’t have wishes and desires about their care.”

Do it when you can express your desires clearly

Mamie, college social work professor

Transcript: “I think it’s important to write them when you know what you’re writing and what you want. I don’t think that has a number to it. But there are some things in the literature that say anybody 40 or up should be sure that these things are in place. I would say that it’s important to do it when you can express your desires clearly and understand them, believe them, and communicate them to other people. That’s the ideal time to do it, in my opinion.”

Make changes as your life changes

Jean, retired educator

Transcript: “After my husband died, that summer I decided I should make a will, should have a living will, should have all of those things taken care of because he left in such a hurry that I thought, now, if something should happen to me, there’s got to be some things done. So, he died in May and I took care of it in June. And so after, as I said earlier, when the boys were finished with college, then I thought it was time to change the person that I had do that, and I started thinking about it, reading more about it, and then when I had my health problem and Nick did a very wonderful, efficient job, I thought definitely that was the one I was going to have, which I had already thought so but it was certainly a proving ground.”

“The conversation is the important piece. The piece of paper reflects simply in concrete ways what the conversation is. So you have to be able to talk about these things before you can write them down on paper.” – Tom, manager of chaplaincy services

There are as many good ways to begin this discussion as there are families and family members. Some families are in the habit of being very direct, and that works for them. Others begin the conversation piecemeal, over a period of time. It can be helpful to use a current news story about end-of-life issues as a starting point: what would you have wanted if you had been Terri Schiavo, for example? It can be equally helpful to tag the topic of advance directives to a conversation about family financial planning. Another promising opening is to engage in a free-flowing discussion about what family members consider essential to enjoying meaningful, satisfying lives.

Read on, or click on the video buttons below for discussion strategies.

Oh, by the way: slipping it into another discussion

Mari, community development specialist

Transcript: “My parents, I see them four or five times a week, so we’re very, very close. We talk about all sorts of things, you know, family, investments, buying homes, interest rates, and so it kind of got worked into one of those discussions, when we were just talking about our life and planning and my parents asking about how much are you putting into your 401K and stuff, and, oh, by the way, this is a part of planning for life and so this is what I’ve done.”

Acknowledge the difficulty

Mamie, college social work professor

Transcript: “If I sense that people are already uptight and angry, I talk about, gee, this is hard. I try to face with them what appears to be their feeling or the kind of behavior that they’re showing and acknowledge that with them. You don’t get into the business until you get that done because if the people are not wanting to talk or they appear to be angry or they’re upset or silent, it is important to acknowledge the difficulty this can be for them and then you move later.”

What brings your life joy and delight?

Tom, manager of chaplaincy services

Transcript: “In some ways, for many of us, the way we live will be reflected in the way we die. So, I think in some ways, rather than trying to have this weighty decision about what are we going to do at the end of life, an easier inroad into that would be let’s talk about life now. What is it that gives meaning and purpose to our lives, to your life? What is it that brings you joy and delight? What would have to change for that delight and that meaning and purpose to change?”

It can’t be just a “business thing”

Mamie, college social work professor

Transcript: “I think it’s important for parents as well as adult children to express their care and love for each other. If parents or children feel that this is just a business thing– That’s why I think it’s important if your parents do not live in the same community or even if they do live in the community, people need to be visiting, they need to have continual involvement so the parents really feel that their children do care about them, and vice versa. I work with adult children as well who really feel that, well, my dad was never there and they really don’t care about me. I think that without that exchange among people the trust factor pops up again and I think you can continue discussions when people really believe that it’s done because you love me, because you really care about me, because you really want to help me, and you’re concerned about me. Many people miss that, they miss it so often.”

“In my family, it’s not spoken. It’s going to be very difficult for my brothers and sister, because it’s like, ‘Don’t worry about that. Let’s not talk about that.” – Magdalena, medical interpreter/translator

Depending on their individual personalities and values as well as on cultural and religious influences, family members often view end-of-life decisions very differently. It’s important to proceed with love and sensitivity and to take these individual differences into account when conversing with your family about living wills and appointment of health-care agents. When you can, bridge geographic distances by talking in person.

Read on, or click on the video buttons below for discussion strategies.

Five children, five unique responses

Tom, manager of chaplaincy services

Transcript: “If I have five children and I love them as my children, I would want to involve them and tell them what my decisions are and expect that since they’re five unique people there are probably going to be five unique responses and talk with each of them about that so they’re all on one page and I’ve honored those differences and their feelings, so when the time comes they can say, you know, I really had a real hard time understanding where Dad was coming from on this but we talked about it and I’m okay with that. When that doesn’t happen, all of that grieving and processing has to occur, but now it occurs in crisis.”

Bridging distance isn’t easy

Magdalena, medical interpreter/translator

Transcript: “And also, and I bring this up again, distance because it’s so typical that somebody from the outside who has not been present throughout the whole process comes and says, well, what about this, we need to do it this other way, and I think that’s where the problems within families arise, when you have an aunt or an uncle or a brother or a sister who has not been present because they live out of town and they might look at it– they have not been through the whole– you know, when you are there, you all move through this current together, and you are kind of building a level of communication and trust and decision-making, but when somebody comes and arrives from the outside and has not been through that process it’s very easy to say, hey, you’re doing it all wrong, I’m looking at it objectively. So, I think that’s, again, communication and seeing how different situations might play because not everybody is present all of the time.”

Different personalities, different perspectives

Frank, computer specialist

Transcript: “And I can see, because of the very differences in the two children we have, and they are very different personalities, that they may disagree when the time comes– that one would want to keep Mom around as long as possible, the other one may be much more detached about it and say, that’s not appropriate, that’s not what she wants. We don’t know that. So I feel like in all of these cases, it’s just good– We have made that choice, we have made very specific kinds of statements that we want to be followed and I’m peaceful that no matter who it is that it will get taken care of that way, as opposed to sort of taking a chance.”

“Who was going to tell me this?” – Vernell, teacher

The conversation hasn’t ended when the paperwork is signed. Letting family members who weren’t part of the discussion know what you’ve decided is an essential part of the process. To spare them avoidable emotional distress during the time the decisions must be put into effect, let them know in advance what you’ve resolved to do and whom you’ve selected as your health-care agent.

Read on, or click on the video buttons below for discussion strategies.

What? Only the hospital knows?

Vernell, teacher [left], and Louard, job trainer

Transcript: LOUARD: It seems like at almost every hospital now, this is a requirement, that you designate if you have a living will or not, and if you do, they have a copy of it on file.

VERNELL: At which hospital?

LOUARD: I have one on file at St. Luke’s and one up here at Mercy.

VERNELL: When was I going to know this?

LOUARD: When I die.

VERNELL: Who was going to tell me this?

LOUARD: I didn’t realize that she wasn’t aware of that.

Face-to-face is best

Frank, computer specialist

Transcript: “Being able to have this conversation face-to-face is just something that feels more appropriate than trying to say or do it on the phone or some other way, because you want to be able to read those quiet moments and those situations and have a little more intimate conversation with, in this case, our children or whoever is going to be acting on your behalf.”

I want to tell them what matters to me

Magdalena, medical interpreter/translator

Transcript: “I’m going to say that we have written some documents, we have completed some documents that are very important for us because they explain how we want to be taken care of on our last days. And I want to talk about that with them, I want them to know what’s important to me, what kind of care I want and don’t want, plus I want them to know how I feel about talking. I want them to come and say, ‘I know you’re dying and let’s talk about it,’ and if you are dying, I would like to be able to do that, too. I don’t want to put those feelings aside and pretend that nothing’s happening.”

“I think a lot of people are scared of actually seeing it written down on paper, but for me it’s more comforting because I don’t have to worry about people guessing what I would have liked.” – Mari, community development specialist

Whether the process of communicating with one another was simple or complex, consistently harmonious or initially upsetting, most families report a feeling of empowerment and a sense of peace once their end-of-life decisions are made and shared.

Read on, or click on the video buttons below for discussion strategies.

When it’s my turn, they’ll know what to do

Lydia, grandmother

Transcript: “Maybe when my husband was alive I was there to decide for him, but when it’s my turn and my husband is not here no more then my kids will have to decide for me, and I know that they’re not going to need an attorney to do that. I know that they already know what to do.”

It’s something that we all face

Nick, physical therapist

Transcript: “It obviously makes you think about those end-of-life issues and it gives you a heavy heart to realize that may well be an issue some day, but it’s something that we all face. We don’t get out of it. It makes you reflect on that briefly and kind of look ahead. Besides that, it made me realize that Mom trusts me enough to involve me in one of the biggest choices of her life, and it’s something I can carry on for her.”

One less thing for them to deal with

Magdalena, medical interpreter/translator

Transcript: “It’s going to make it easier for them because they are not going to have to be making tough decisions. The decision is already made for them and then they can– they are going to have lots of– well, who knows? They could have a lot of things to deal with and this is a very important thing that they do not have to make the decisions and deal with it.”

Return to the Communicate Your Advance Directives for Health Care lesson.