When someone dies owning property (real property as well as tangible and intangible personal property), the law provides a legal procedure for settling the estate. This procedure, commonly called “probate,” involves:

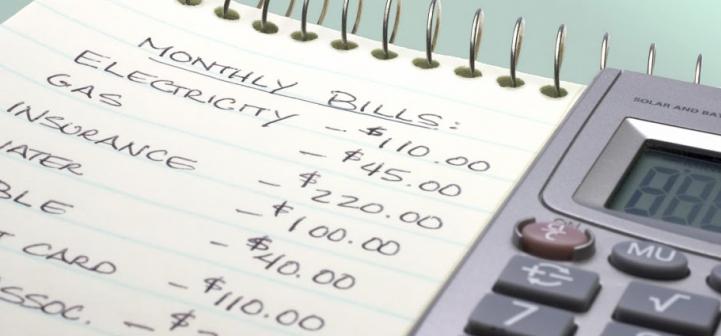

- determining what property the person owned and its value

- determining what debts the person owed

- distributing or assigning title of the person’s property to its new rightful owners

Federal and state estate taxes are also determined, although these must be paid even if no probate procedure is required.

Not all property is subject to the probate process. Examples include:

- property held in a living trust (although similar steps are generally followed by the trustee—but without court supervision)

- property held in joint tenancy with rights of survivorship

- property with a named beneficiary (unless the estate is the beneficiary); for example, life insurance cash value, Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs), U.S. savings bonds

After notice is given, state law will allow a period of time—varying from state to state—for creditors to make claims against the estate for debts owed them by the decedent (the person who died). The estate must remain open at least as long as the time allowed for filing claims against it. In certain circumstances, with court approval, an estate may be administered as a “simplified estate” for which direct court supervision of the personal representative’s activities is not generally required, except to open and close the estate.

In a few cases, no probate proceeding is required. An example is if the decedent had no outstanding debts (or if any debts are assumed and paid by other people) and had no interest in property subject to the probate process. Another example is if the value of the estate is under a specified monetary amount.

Lesson Contents

III. Power of Attorney: Planning for Incapacity

IV. Property Transfer: Documents and Legal Arrangements

VI. The Probate Process

VII. Personal Representative: To Carry Out Your Wishes

VIII. Gifting and Tax Strategies

X. How to Hire and Work with an Attorney

Prepare Your Estate Plan belongs to a series called Legally Secure Your Financial Future. The series also includes information to help you organize important household papers and to communicate your health-care wishes.